The Australian Constitution in focus

The Australian Constitution is the legal framework for how Australia is governed. This paper explores in detail the history of the Constitution, its key features and the High Court’s role in interpreting it.

So What is a constitution?

Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act, 1900: Original Public Record Copy (1900).

PARLIAMENT HOUSE ART COLLECTION, ART SERVICES PARLIAMENT HOUSE

A constitution is a set of rules by which a country or state is run.

Some countries have unwritten constitutions which means there is no formal constitution written in one particular document. Their constitutional rules come from a number of sources. Britain sources its constitution from a number of important laws as well as principles decided in legal cases and conventions. New Zealand has a number of documents that comprise it’s constitution.

Other countries have formal written constitutions in which the structure of government is defined and the powers of the nation and the states are written in one single document. These systems may also include unwritten conventions—traditions—and constitutional law which can inform how the constitution is interpreted. Australia, India and the United States are examples of countries with a written constitution.

Some constitutions may be amended—changed—without any special process. The documents that make up the New Zealand Constitution may be changed simply by a majority vote of its Parliament. In other countries a special process must be followed before their constitution can be changed. Australia has a constitution which requires a referendum in order to change it.

The Commonwealth Of Australia Constitution.

The Commonwealth of Australia Constitution is the set of rules by which Australia is governed. Australians voted for the Constitution in a series of referendums. The Constitution establishes the composition of the Australian Parliament, describes how Parliament works and what powers it has. It also outlines how the federal and state Parliaments share power, and the roles of the executive government and the High Court of Australia . It took effect on 1 January 1901.

In addition to the national Federal Constitution, each Australian state has its own constitution each of which is subject to the Federal Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act.

The Australian Capital Territory and Northern Territory have self-government Acts which were passed by the Australian Parliament.

Constitutional conventions

For at least 50 000 years, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have lived on these lands and practiced traditional cultures and languages. From the late 1700s, British colonies were established. By the late 1800s, these colonies had their own parliaments but were still subject to the law-making power of the British Parliament.

During the 1890s colonial representatives came together at special meetings called ‘constitutional conventions’ to draft a constitution which would unite the colonies as one nation and provide for a new level of national government.

Each Australian colony sent delegates to the conventions. By 1898 the delegates had agreed on a draft constitution which they took back to their respective colonial parliaments to be approved.

Passing the Constitution

The final draft of the Constitution was approved by a vote of the people in referendums held in each colony between June 1899 and July 1900.

The Constitution had to be agreed to by the British Parliament before the colonies could unite as a nation. An Australian delegation travelled to London to present the Constitution to the British Parliament.

After negotiating some changes, the British Parliament passed the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Bill in July 1900.

Queen Victoria approved the bill on 9 July 1900 by signing the Royal Commission of Assent and the bill became the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act 1900. Section 9 of this Act contained the Constitution which stated that on and after 1 January 1901, the colonies of New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia, Queensland and Tasmania would be united and known as the Commonwealth of Australia. Western Australia agreed to join the other colonies in a referendum held on 31 July 1900—2 weeks after the Act was passed.

After federation in 1901 Australia still had constitutional ties with Britain, particularly in the areas of foreign policy and defence. Since then the British and Australian parliaments have passed a number of laws which have given Australia greater constitutional independence.

However were these changes done so legally and constitutionally according to the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act.

For example, in 1942 the Australian Parliament passed the Statute of Westminster Adoption Act 1942 which meant Australian laws could no longer be over-ruled by the British Parliament.

The Australia Act 1986 removed all remaining legal links between the Australian and British governments.

These acts both recived no Referendums.

These act were done without the approval of the people.

Key features of the Constitution

The Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act 1900 granted permission to the 6 Australian colonies, which were still subject to British law, to form their own national government in accordance with the Constitution. The Act consists of a preamble and 9 clauses, of which clause 9 is the original Australian Constitution. The Constitution consists of 8 chapters and 128 sections.

Chapter I describes the composition and powers of the Australian Parliament, which consists of the Queen and a bicameral legislature with:

- Single-member representation for each electorate for the House of Representatives

- Multi-member representation for each state for the Senate.

Chapter I contains sections 51 and 52, which list most of the areas in which the Australian Parliament can make laws. The Australian Parliament can make laws on a range of issues (such as immigration and pensions), but the Constitution allows other powers (such as providing roads and transport) to remain with the states.

Chapter II describes the power of the most formal elements of executive government, including the Queen, Governor-General and the Federal Executive Council .

Chapter III provides for the creation of federal courts, including the High Court of Australia, which is the final court of appeal. The High Court can interpret the law and settle disputes about the Constitution.

Chapter IV deals with financial and trade matters.

Chapters V and VI outline the relationship between the Australian Parliament, and the states and territories. Importantly, chapter 5 states that if the Australian Parliament and a state parliament both pass laws on the same subject and these laws conflict, then the national law overrides the state law. Section 122 in Chapter 6 gives the Australian Parliament the power to override a territory law at any time. It also allows the Australian Parliament to make laws for the representation of the territories.

Chapter VII describes where the capital of Australia should be and the power of the Governor-General to appoint deputies.

Chapter VIII describes how the wording of the Constitution can be changed by referendum.

The Australian Constitution does not include a bill of rights. However, some human rights are mentioned, including the right to compensation if the government acquires your property (section 51 (xxxi)), guaranteed trial by jury for federal offences (section 80) and freedom of religion (section 116).

The sections of the Australian Constitution.

PARLIAMENTARY EDUCATION OFFICE (PEO.GOV.AU)

The Constitution and the High Court of Australia

People are allowed to test the meaning and application of the Australian Constitution. The High Court of Australia interprets the Constitution and settles disputes about its meaning. It has the power to consider national and state laws and determine if such laws are within the powers granted in the Constitution to the relevant level of government. The High Court can invalidate any law or parts of a law it finds to be unconstitutional.

Sometimes the High Court is asked to decide whether it is the Australian Government or a state government which has the authority and responsibility to deal with a matter. At other times, because the Constitution provides specific limits to what the Australian Government has the power to do, the High Court may be asked to decide whether a law made by the Australian Government is within that power.

How the Constitution can be changed

Changing the Australian Constitution – double majority.

PARLIAMENTARY EDUCATION OFFICE (PEO.GOV.AU)

The Australian Constitution can be changed by referendum according to the rules set out in section 128 of the Constitution. A proposed change must first be approved as a bill by the Australian Parliament before it is put to the Australian people to decide.

A referendum is a national ballot on a question to change the Constitution. In a referendum the Parliament asks each Australian on the electoral roll to vote. To be successful, the proposed change must be agreed:

- by the majority of people across the nation

- by the majority of people in a majority of states.

This is called a double majority.

Since the first referendum in 1906, Australia has held 19 referendums in which 44 separate questions to change the Australian Constitution have been put to the people. Only 8 changes have been agreed to.

Successful referendums have included:

- The 1946 referendum which allowed the Australian Government to provide social welfare payments.

- The 1967 referendum (in which 90.77 per cent of people voted ‘yes’) which gave the Australian Parliament the power to make special laws for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

- The 1977 referendum which gave the people of the territories the right to vote in referendums, changed the way casual Senate vacancies were filled and forced federal judges to retire at 70 years of age.

Unsuccessful referendums have included:

- The 1951 referendum which sought to give the Australian Parliament the power to make laws about communism and communists.

- The 1999 referendum which asked whether Australia should become a republic .

There are more unsuccessful and successful referendums here

Referendums in the Commonwealth of Australia.

How the Constitution is interpreted has also changed and evolved, even without changes being agreed to in referendums. These changes have not changed the words of the Constitution but have been brought about by High Court decisions. Two examples are:

- The Australian Government’s increased power to collect income tax has meant it has a much greater ability to raise money than the states. The Australian Government partly redistributes this money in the form of grants to the states. This has allowed the Australian Government to gain control of areas of responsibility the states previously controlled—for example, higher education.

- The Australian Government’s power over foreign affairs (section 51(xxix)) has meant laws to implement international treaties can be applied to the states in areas which were previously controlled by the states alone (such as environmental protection).

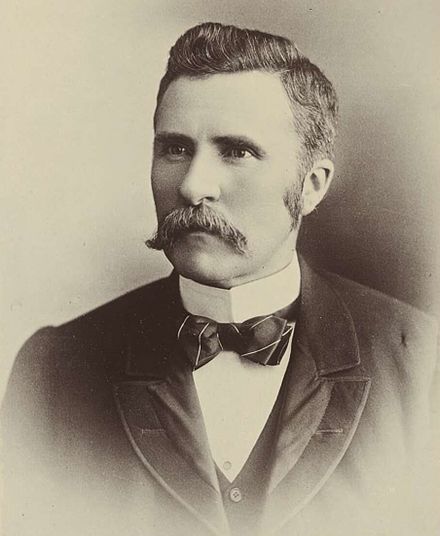

This evolutionary change in interpretation should never have been allowed as the framemakes and forefathers of our Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act in fact produced a annotated Commonwealth of Australia Constitution with a complete guide as to how our Constitution be interpreted.

See Link Below.

Annotated Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act.

There are currently two versions getting around one green one red.

Its best to stay clear of the green molested version of the quick and garran.

The Red is the Original unmolested version.

To see the online version of our Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act uk see Link Below

The Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act uk version.

Federation

In the mid-19th century, a desire to facilitate co-operation on matters of mutual interest, especially intercolonial tariffs, led to proposals to unite the separate British colonies in Australia under a single federation. However, impetus mostly came from Britain and there was only lacklustre local support. The smaller colonies feared domination by the larger ones; Victoria and New South Wales disagreed over the ideology of protectionism; the then-recent American Civil War also hampered the case for federalism. These difficulties led to the failure of several attempts to bring about federation in the 1850s and 1860s.

By the 1880s, fear of the growing presence of the Germans and the French in the Pacific, coupled with a growing Australian identity, created the opportunity for establishing the first inter-colonial body, the Federal Council of Australasia, established in 1889. The Federal Council could legislate on certain subjects, but did not have a permanent secretariat, an executive, or independent source of revenue. The absence of New South Wales, the largest colony, also diminished its representative value.

Henry Parkes, the Premier of New South Wales, was instrumental in pushing for a series of conferences in the 1890s to discuss federalism – one in Melbourne in 1890, and another (the National Australasian Convention) in Sydney in 1891, attended by colonial leaders. By the 1891 conference, significant momentum had been built for the federalist cause, and discussion turned to the proper system of government for a federal state. Under the guidance of Sir Samuel Griffith, a draft constitution was drawn up. However, these meetings lacked popular support. Furthermore, the draft constitution sidestepped certain important issues, such as tariff policy. The draft of 1891 was submitted to colonial parliaments but lapsed in New South Wales, after which the other colonies were unwilling to proceed.

In 1895, the six premiers of the Australian colonies agreed to establish a new Convention by popular vote. The Convention met over the course of a year from 1897 to 1898. The meetings produced a new draft which contained substantially the same principles of government as the 1891 draft, but with added provisions for responsible government. To ensure popular support, the draft was presented to the electors of each colony. After one failed attempt, an amended draft was submitted to the electors of each colony except Western Australia. After ratification by the five colonies, the Bill was presented to the British Imperial Parliament with an Address requesting Queen Victoria to enact the Bill.

Before the Bill was passed, however, one final change was made by the imperial government, upon lobbying by the Chief Justices of the colonies, so that the right to appeal from the High Court to the Privy Council on constitutional matters concerning the limits of the powers of the Commonwealth or States could not be curtailed by parliament. Finally, the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act was passed by the British Parliament in 1900. Western Australia finally agreed to join the Commonwealth in time for it to be an original member of the Commonwealth of Australia, which was officially established on 1 January 1901.

In 1988, the original copy of the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act 1900 from the Public Record Office in London was lent to Australia for the purposes of the Australian Bicentenary. The Australian government requested permission to keep the copy, the British Parliament agreed by passing the Australian Constitution (Public Record Copy) Act 1990 and the copy was given to the National Archives of Australia.

Amendments

As mentioned above, amendment of the Constitution requires a referendum in which the proposed amendment is approved by a majority in each of a majority of the States, as well as nationally.

Forty-four proposals to amend the Constitution have been voted on at referendums, of which eight have been approved. The following is a list of amendments which have been approved.

- 1906 – Senate Elections – amended Section 13 to slightly alter the length and dates of Senators’ terms of office.

- 1910 – State Debts – amended Section 105 to extend the power of the Commonwealth to take over pre-existing state debts to debts incurred by a state at any time.

- 1928 – State Debts – inserted Section 105A to ensure the constitutional validity of the Financial Agreement reached between the Commonwealth and State governments in 1927.

- 1946 – Social Services – inserted Section 51 (xxiiiA) to extend the power of the Commonwealth government over a range of social services.

- 1967 – Aborigines – amended Section 51 (xxvi) to extend the power of the Commonwealth government to legislate for people of any race to Aborigines; repealed Section 127 which stated that “In reckoning the numbers of the people of the Commonwealth, or of a State or other part of the Commonwealth, aboriginal natives shall not be counted.”

- 1977

- Senate Casual Vacancies – part of the political fallout of the constitutional crisis of 1975; formalised the convention, broken in 1975, that when a casual vacancy arises in the Senate, the state parliament concerned, if it chooses to fill the vacancy, must choose the replacement from the same party as the departing Senator if that party still exists.

- Referendums – amended Section 128 to allow residents of the Territories to vote in referendums, and be counted towards the national total.

- Retirement of Judges – amended Section 72 to create a retirement age of 70 for judges in federal courts.

The role of conventions

Alongside the text of the Constitution, the Statute of Westminster and the Australia Acts, and letters patent issued by the Crown, conventions are an important aspect of the Constitution, which have evolved over the decades and define how various constitutional mechanisms operate in practice.

Conventions play a powerful role in the operation of the Australian constitution because of its set-up and operation as a Westminster system of responsible government. Some notable conventions include:

- While the constitution does not formally create the office of Prime Minister of Australia, such an office developed a de facto existence as head of the cabinet. The Prime Minister is seen as the head of government.

- While there are few constitutional restrictions on the power of the Governor-General, by convention the Governor-General acts on the advice of the Prime Minister.

However, because conventions are not textually based, their existence and practice are open to debate. Real or alleged violation of convention has often led to political controversy. The most extreme case was the Australian constitutional crisis of 1975, in which the operation of conventions was seriously tested. The ensuing constitutional crisis was resolved dramatically when the Governor-General Sir John Kerr dismissed the Labor Prime Minister Gough Whitlam, appointing Liberal opposition leader Malcolm Fraser as caretaker Prime Minister pending the 1975 general election. A number of conventions were said to be broken during this episode. These include:

- The convention that, when the Senator from a particular State vacates his or her position during the term of office, the State government concerned would nominate a replacement from the same political party as the departing Senator. This convention was allegedly broken by first the Lewis government of New South Wales and then by the Bjelke-Petersen government of Queensland who both filled Labor vacancies with an independent and a Labor member opposed to the Whitlam government respectively.[12]

Note: The convention was codified into the Constitution via the national referendum of 1977. The amendment requires the new Senator to be from the same party as the old one and would have prevented the appointment by Lewis, but not that by Bjelke-Petersen. However, the amendment states of the appointee that if “before taking his seat he ceases to be a member of that party…he shall be deemed not to have been so chosen or appointed”. Bjelke-Petersen appointee Albert Patrick Field was expelled from the Labor Party before taking his seat and would therefore have been ineligible under the new constitutional amendment.[13]

- The convention that, when the Senate is controlled by a party which does not simultaneously control the House of Representatives, the Senate would not vote against money supply to the government. This convention was allegedly broken by the Senate controlled by the Liberal-Country party coalition in 1975.[12]

- The convention that a Prime Minister who cannot obtain supply must either request that the governor general call a general election, or resign. This convention was allegedly broken by Gough Whitlam in response to the Senate’s unprecedented refusal

Interpretation

Australian constitutional law

In line with the common law tradition in Australia, the law on the interpretation and application of the Constitution has developed largely through judgments by the High Court of Australia in various cases. In a number of seminal cases, the High Court has developed several doctrines which underlie the interpretation of the Australian Constitution. Some examples include:

- Separation of powers – The existence of three separate chapters dealing with the three branches of government implies a separation of powers, similar in principle to that of the United States but unusual for a government within the Westminster system.[15] Thus, for example, the legislature cannot purport to predetermine the legal outcome, or to change the direction or outcome, of a court case.

- Division of powers – Powers of government are divided between the Commonwealth and the State governments, with certain powers being exclusive to the Commonwealth, others being concurrently exercised, and the remainder being held by the States.

- Intergovernmental immunities – Although the Engineers’ case[16] held that there was no general immunity between State and Commonwealth governments from each other’s laws, the Commonwealth cannot enact taxation laws that discriminated between the States or parts of the States (Section 51(ii)), nor enact laws that discriminated against the States, or such as to prevent a State from continuing to exist and function as a state ().[17]

The vast majority of constitutional cases before the High Court deal with characterisation: whether new laws fall within a permissible head of power granted to the Commonwealth government by the Constitution.[citation needed]

Protection of rights

See also Australian constitutional law – Protection of rights

The Australian Constitution does not include a Bill of Rights. Some delegates to the 1898 Constitutional Convention favoured a section similar to the Bill of Rights of the United States Constitution, but the majority felt that the traditional rights and freedoms of British subjects were sufficiently guaranteed by the Parliamentary system and independent judiciary which the Constitution would create. As a result, the Australian Constitution has often been criticised for its scant protection of rights and freedoms.

Some express rights were, however, included:

- Right to trial by jury – Section 80 creates a right to trial by jury for indictable offences against Commonwealth law. However, the Commonwealth is left free to make any offence, no matter how serious the punishment, triable otherwise than on indictment. As Justice Higgins said in R v Archdall (1928): “if there be an indictment, there must be a jury, but there is nothing to compel procedure by indictment”.[18] In later cases, the High Court has split: some judges have attempted to find a right, on the basis that no constitutional provision may be understood in a way that renders it empty; others have thought that this would inject content, beyond the boundaries of judicial interpretation.[19] The Court has been flexible on the meaning of “jury”: there will be a “jury”, although not all members are male as would have been the Framers’ understanding; but there will not be a valid decision by a jury, if there is a majority verdict (even though that is permitted in some states). In practice, however, no major issue of abuse of this uncertainty has been raised.

- Right to just compensation – Section 51(xxxi) creates a right to compensation “on just terms” for “acquisition of property” by the Commonwealth from any state or person.[20] The “acquisition of property”, itself, is not restricted, but the High Court has understood the expression broadly so as to give a broad entitlement to compensation.

- Right against discrimination on the basis of out-of-State residence – Section 117 prohibits disability or discrimination in one state against a resident of another state. This is interpreted widely: the restriction will be invalid if it treats an out-of-state resident more onerously than if they were resident within the state.[21][22] However, it does not prohibit states from imposing residential requirements where these are required by the State’s autonomy and its responsibility to its people; a state may, for example, permit only residents to vote in state elections.

There are also some guaranteed freedoms, reasons why legislation that might otherwise be within power may nonetheless be invalid. These are not rights of individuals, but limitations upon legislative power. However, where legislation that would adversely affect an individual is found to be invalid for such a reason, the effect for the individual is similar to vindicating a right of that individual. There is one express “freedom”.

- Freedom of religion – Section 116 creates a freedom of religion, by prohibiting the Commonwealth (but not the states) from making “any law for establishing any religion, or for imposing any religious observance, or for prohibiting the free exercise of any religion”. This section is based on the First Amendment to the US Constitution, but is weaker in operation. As the states retain all powers they had as colonies before federation, except for those explicitly given to the Commonwealth, this section does not affect the states’ powers to legislate on religion. Section 116 has never been successfully invoked. A deterrent to invoking it is, as the High Court has found, the uncertain meaning of “religion”.

There is also one implied right that is agreed upon by a majority judgment of the High Court. An implied right is one that is not written explicitly into the wording of the Constitution, but that the High Court has found to be implied by reading two or more sections together. The implied right of freedom of political communication is discussed below.

In addition to individual rights explicitly written into the Constitution and found to be implied by sections within it there is a final category of rights known as ‘structural protections’. Rather than being individual rights, these are broad protections for the community as a whole, taken from the systems and principles created by and underpinning the text and structure of the Constitution as a whole. One of the more well-known of these protections is the community right to a democratically elected parliament, commonly thought of as a limited “right” to vote, which is discussed below.

The following are implied rights or freedoms:

- Implied freedom of political communication – In 1992 and 1994, the High Court found that the Constitution contained an “implied freedom of political communication”, in a series of cases including Australian Capital Television[23] and Theophanous.[24] These were majority decisions, but the existence of the freedom was unanimously confirmed in Lange v ABC.[25] Rejecting wider suggestions in the earlier cases, Lange decided that the freedom can be found only in the “text and structure” of the Constitution and not by reference to any general legal or political principles, for example that of “democracy”. In these terms, the freedom was found to be a necessary concomitant of the provision in Constitution sections 7 and 24 that the houses of the Commonwealth Parliament shall be “chosen by the people”; the people must not be restricted from communicating with each other and with their representatives on all matters that may be relevant to that choice. The freedom was deemed to extend into the states and territories, on the basis that nationally there is a single sphere of political communication. The US First Amendment refers to “speech”, which may be oral or written but is limited as to protection of non-verbal expression (such as burning a draft card). The High Court has avoided that limitation by preferring the broader term “communication”.[26] Nonetheless, the freedom is not absolute: legislation that “burdens” the freedom of political communication will nevertheless be valid if it “proportionately” pursues some other legitimate purpose (such as public safety).

- Implied right to vote – In 2007, in Roach v Electoral Commissioner,[27] the High Court held that Constitution ss7 and 24, by providing that members of the House of Representatives and the Senate be “directly chosen by the people”, created a limited right to vote. This entailed the guarantee of a universal franchise in principle, and limited the Federal Parliament’s legislative power to modify that universal franchise. In the case, a legislative amendment to disqualify from voting all prisoners (as opposed to only those serving sentences of three years or more, as it was before the amendment) was struck down as contravening that right. The structural protection of a democratically elected parliament prevents the Commonwealth from taking away the right to vote from sections of the community without a substantial and legitimate reason, but it does not grant each and every individual a “right” to vote in elections. The issue of implied right to vote came up again in Rowe v Electoral Commissioner.[28]

Attempts in High Court cases to find further implied rights or freedoms have not been successful. Implication of a freedom of association and a freedom of assembly, independently or linked to that of political communication, has received occasional judicial support but not from a majority in any case.

In any case our fundamental unalienable rights as free sovereign men and women are indeed protected in the common law, bill and declaration of rights uk, magna carta and the king james bible foundations of our indisolvable federal commonwealth of Australia.

The Constitution is an instrument created to limit Government powers and Display that the people reign supreme not Government.

You will find a list of fundamental unalienable rights as free sovereign men and women below including a link to the origins of those rights.

Fundamental Unalienable rights

Origins of our fundamental rights.

State constitutions of the commonwealth of Australia

In Australia, each state has its own constitution.[1] Each state constitution preceded the Constitution of Australia as constitutions of the then separate British colonies, but all the states ceded powers to the Parliament of Australia as part of federation in 1901.

List of state constitutions

The following is a list of the current constitutions of the six states of Australia. Each entry shows the ordinal number of the current constitution, the official name of the current constitution, and the date on which the current constitution took effect.

Notice the date of effect changes.

| No. | State | Date of effect | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | Constitution of New South Wales | 1856 | |

| 2nd | Constitution of Queensland | 2001 | |

| 1st | Constitution of South Australia | 1934 | |

| 1st | Constitution of Tasmania | 1856 | |

| 2nd | Constitution of Victoria | 1975 | |

| 1st | Constitution of Western Australia | 1890 |

we hope this information helps others thanks for reading .

RELATED ARTICLES

- State government government of a federated entity (state, province, …) in a federal state

- Fiscal imbalance in Australia

- Politics of Western Australia